Titanium Chainplates on Sailboats started to be installed on sailboats, before Brick House was dismasted in 2011, because that’s when we replaced our stainless steel chain plates with titanium chainplates, titanium Clevis pins, titanium tangs, and although we were semi early adopters, we were not the first to do this. We were so impressed and the prices of titanium came down so much, 7 years later we replaced our bow roller-Stemplate with titanium too. If we could install titanium rigging, I think we would. Our Titanium components, 8 years later, look like its all brand new. There have been no issues at all with corrosion. They are the shiny jewels on this old sailboat, the part sure to never fail. But there is one problem with thinking that our mast should now stay up forever. One more thing a sailor must think about if sailing around the world, and has replaced he standing rigging, right down to the chainplates.

In a few minutes, we will be posting Another DIY Sailing/sailboat video about something else that affects the integrity of your rig, that could result in a dismasting even if you DO have titanium chainplates, or all new rigging. It will be a 2 part series. So be sure you are subscribed on YouTube to Patrick Childress Sailing to find out all about it, and be notified. It’s not that difficult to guess perhaps, but something many many of us forget to examine on a regular basis.

Patrick wrote an excellent article for Practical Sailor, and it is on the Allied Titanium Website since this is who we worked with to make the chainplates out of Grade 5 Titanium, the only grade of titanium Patrick can recommend for these high load components.

Click Here for the entire article in PDF format, or if you prefer, here are photos of each page.

Here is most of the article in text, without photos, in case your internet doesn’t allow the photos above, or if the link doesn’t work.

Here is most of the article in text, without photos, in case your internet doesn’t allow the photos above, or if the link doesn’t work.

Through the commotion of a 30- knot squall, I heard the chainplate pop. It was not an unusually loud pop. The result was impressive, nonetheless. What once was, just a few moments earlier, the tallest part of the mast on our Valiant 40 Brick House was now the lowest, scraping the tops of waves in the middle of the South Pacific Ocean. The dispirited look on my wife Rebecca’s face made the terrible situation even more depressing. I swore, in rebuilding our rig, we would never again be the victim of the weaknesses stainless steel can hide. We would replace our chain plates, toggle pins, and mast tangs with titanium.

In name alone, the word titanium evokes images of superhuman strength. The metal is aptly named after the Titans, the race of powerful Greek gods, descendants from Gaia and Uranus.

Titanium is whitish in color and the fourth most abundant metallic element in the Earth’s crust. Ninety-five percent of mined titanium becomes titanium dioxide. Titanium dioxide is the white pigment added to all types of paints. Titanium dioxide makes paper bright

mined titanium is used to make metal components that must be light, strong, and resistant to heat and corrosion. This five percent, though small, represents a rapidly growing market.

Landing gear of large commercial aircraft, like the 747 and 777, are made of titanium. No other metal has the resiliency to repetitive shock loading and offers the weight savings of titanium. Nearly 80 percent of the structure of the Lockheed SR 71 reconnaissance plane, the highest fly- ing, fastest plane ever built, is made of titanium. From drill bits to eyeglass frames to tennis rackets to artificial heart valves, titanium metal is in our lives every day.

Of particular interest to sailors is titanium’s resistance to galvanic corrosion. Only silver, gold, and graph- ite are more noble than titanium. For titanium to be even slightly affected by sea water, the water must first be heated to over 230 degrees. Cryogenic temperatures will not affect the perfor- mance of titanium. It has the highest strength-to-weight ratio of any metal and is non-magnetic. Titanium is up to 20 times more scratch resistant than

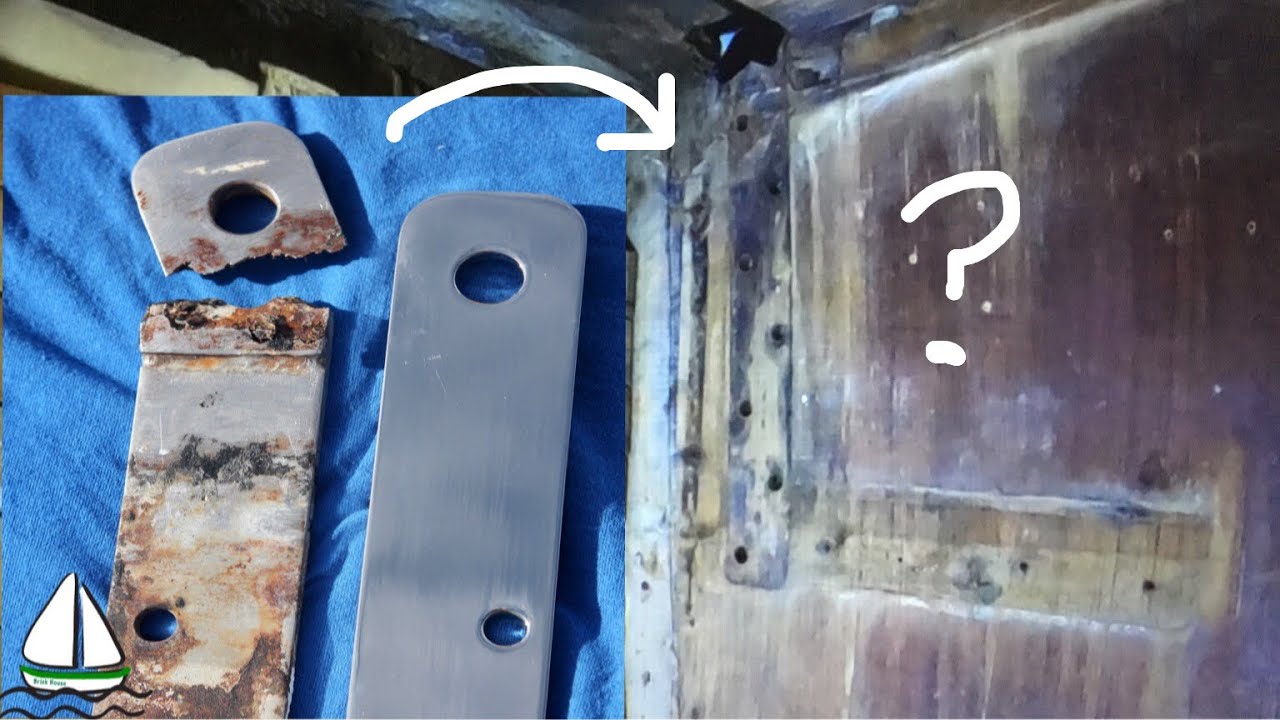

The new titanium chainplate shines brilliantly among the stainless steel ones it replaced, including the one that broke.

white and is the white paste that some sailors like to smear on their nose on a sunny day to provide a physical barrier against UV radiation. Our white homes and sailboats are resplendent in white titanium.

stainless steels.

The more one considers the physical

characteristics of titanium, and how perfectly suited it seems for marine ap- plications, the more one might wonder why we don’t see more of it in our boats. Part of the problem is the relative cost of titanium alloys, but a second factor is probably more to blame for titanium’s scarcity in the marine market. Titanium fabrication is a highly specialized field that requires specialized equipment. You can’t just hire your local welder to go out and build you a titanium arch.

Marine-grade titaniuM

The performance characteristics of ti- tanium will change greatly with its al- loying of other metals for customized work. Commercially pure titanium is typically rated from Grade 1 to Grade 4, with each higher grade correspond- ing to increasing strength levels. Some of these grades are used to withstand boiling acids; some are used for heat and corrosion-resistant applications such as heat exchangers and chemical process- ing tanks.

The marine industry standard is Grade 5, Ti-6Al-4V. This alloy is 90 percent titanium, 6 percent aluminum, and 4 percent vanadium. The alloy is so widely used that it represents 75 percent of all titanium alloys produced. Grade 5 has a yield strength over 31⁄2 times greater than 316 stainless steel, yet weighs only 56 percent as much. Yield strength, sometimes called engineering strength, is the amount of pressure or force a material can take before chang- ing shape without returning to its origi- nal shape. But titanium is also nearly twice as resilient as steel, so it will flex and return to its original shape under the same loads that might permanently bend a comparable piece of stainless.

Not only is titanium strong, it is high- ly resistant to chemicals. Being a reactive metal, it spontaneously forms an oxide film whenever there is any amount of water or air in the environment. That oxide film eliminates the possibility of crevice corrosion or stress-corrosion cracking. Titanium is immune to gal- vanic corrosion when immersed in seawater, but like stainless steel, tita-

nium may encourage electrolysis of a less noble metal it is in contact with. Profurl roller-furling uses ti- tanium screws that pass through the alu- minum body of their housings to mini- mize galvanic corro- sion. Still, an isolator like LanoCote (www. lanacote.com) or Tef- Gel (www.tefgel.com) needs to be applied to the threads of the titanium screws, the same as one would do if stainless-steel screws were used. Above the waterline, Titanium in contact with 316 stainless is of no greater concern than where stainless- steel threaded studs screw into bronze turnbuckles. Working sheets of titanium into yacht parts requires the same tools that are used for forming stainless steel. Drilling requires sharp cobalt drill bits turning at similar speeds used for stainless steel and plenty of lubricant (olive oil works) for cooling.

Sawing and grinding also require sharp tools with good chip removal. Cutting with waterjet and laser is the most effective. But shears that slice through thick 316 stain- less steel will stop when forced against equally thick plates of titanium.

When bending titanium, the bend area must first be heated to around 800 degrees, as the yield strength drops to about 40 percent at that temperature. If titanium is overheated to the point where it glows, it can react with air and become oxygen embrittled. For this same reason, cutting titanium with oxyacetylene flame is not recommended.

The crew of Brick House waited until morning to begin the tricky process of removing the mainsail after a stainless steel chaiplate failed, causing the mast to snap.

experienced. Air will contaminate the weld causing discoloration and brittle- ness. An inert gas like 99.99 percent pure argon must shield the area on both sides of the weld till the material cools below 800 degrees.

The physical properties of titanium are exactly those that are needed in sail- boat rigging as it pounds through ocean waves. Unlike stainless steel, titanium will not deteriorate, or crack, or rust, or have an unexpected catastrophic failure. Once installed on a sailboat with titanium fasteners, a properly sized titanium chainplate will never need polishing, although welds should be checked.

So why has the leisure marine industry been slow to use titanium?

For years, the high cost of titanium made it an aerospace metal for govern- ment projects and commercial airplane parts where there was no alternative metal to use. That high cost was an unforeseen result of the protectionist Berry Amendment. The 1941 legislation made it mandatory for the U.S. govern- ment to purchase only 100 percent U.S. manufactured goods intended for mili- tary use. Titanium was soon added to the list of specialty metals covered un-

der the Berry Amendment. This gave the few largest U.S. titanium makers a lock on the world’s largest titanium customer, the U.S. military. This elimi- nated competition and kept the price of titanium flying high.

This grip on the U.S. titanium market also eliminated any need to streamline the smelting process. But when the U.S. military shifted from a strategic bomber defense to a missile defense, the use of expensive titanium plummeted and some U.S. producers went out of business. The few that remained could only survive by keeping the price of titanium high for their government customers.

According to Christopher Greimes, chief executive officer of Allied Titanium, with the current economic downturn, the U.S. military would like to remove titanium from the specialty metals list as they need more and cheaper titanium, not just for use in aircraft, but for use in armor plating for ground troops. The U.S. titanium producers are strongly lob- bying to keep titanium on the specialty metals list. President Barack Obama is allowing an unsigned repeal of titanium from that list to collect dust on his desk. Meanwhile, other countries like China, Japan, and Russia have been ramping up their refined smelting technologies and producing less costly titanium for the world market.

As world production and use in the leisure marine market increases, the price of titanium should continue to fall. One day, titanium will replace stainless steels. The savings to insurance compa- nies that will no longer have to pay for expensive boat losses and the increased safety to sailors will be enormous.

Practical Matters

The problem for an individual boat owner is that the local welding shops do not carry a stock of titanium sheets and to order small lots and fabricate a few parts can be time consuming and ultimately not the price one would hope to pay. There are large outlets for titanium um fabrication that solve the problem. A company such as Allied Titanium has fabricating outlets in Europe, U.S., and China. A boat owner can log onto the Allied website to view thousands of items such as nuts, bolts and chain- plates. If a particular boat part is not listed, it can be fabricated.

We needed 10 new chainplates, all of the same design, and a combination bow roller/chainplate assembly. Since there had been no previous purchase for these items for a Valiant 40, we had options on how to enter the information into the Allied database.

First we logged in and became a customer, creating a user name, and pass- word. We could trace the chainplate outline and bolthole placement onto stiff paper, noting the thickness of the original plate and the desired finish such as sandblasted or polished. However,

we thought sending an actual chainplate would be better. Allied then hand drafted our chainplate into its 3D system. We could watch online as the chainplate was received at Allied and made its way through the design process. If a customer supplies design in a 3D CAD file in SolidWorks, Rhino, or 3D Auto CAD, there is no drafting charge at all. If the customer supplies a two-dimensional drawing that is properly dimensioned, with tolerances, finish, etc. and they al- low Allied to add their part to the Unique Product Database (UPD), then there is no charge for conversion to a SolidWorks 3D CAD file.

At Allied, the part name, tolerances, finish, titanium grade, etc., are entered into the UPD, creating both an item number and a temporary UPD number. The customer then approves the drawings. When the design process is completed and the customer approves the price, the part design is then transmitted to one of Allied Titanium’s factories, some of which are in China.

The immediate hesitation of many boat owners is the idea of having anything made in China. Japan produced a lot of junk after World War II, then learned to do it right and has equaled or outdistanced America in many manufacturing fields. So too, China is refining the quality of its products.

As Practical Sailor pointed out in the August 2011 look at mainsails, sails made in China are often rebranded and sold by the top sailmakers in America. Nearly all stainless steel wire rigging used on yachts now comes from China or Taiwan. When it comes to Chinese titanium, that metal has been strategic in the past, requiring strict quality control by the Chinese military. This means that Chinese factories and workers know how to make titanium products properly. The Chinese are now cashing in on the world demand for titanium faster than Obama can sign his name.

According to Allied, “Each time titanium is smelted, resmelted, or milled, it must have mechanical and chemical tests done on the lot. When a customer requests a ‘certs,’ the results from the last certification is pro- vided. In most cases, this is the mill

certification.” However, some U.S. customers of Allied send a sample of their purchase to an independent lab for backup testing. “In all cases, our 6-4 titanium parts have tested above 128,000 psi yield strength. If a customer has an issue with a certain country, we can manufacture their parts in another country (at a different price, of course),” Greimes said.

When the part is complete, it is sent directly from the manufacturing plant

to the Allied Titanium Quality Assur- ance Department in the United States via Fedex, UPS, or DHL. After passing quality assurance, it is shipped directly to the customer The street price for one of our chain- plates was $260 at the time of this writing. We saved considerably by negotiat- ing a price for all ten to be made at the same time. From the day we mailed our old chainplate to Allied Titanium to the day 10 titanium chainplates arrived in our hands, took 65 days.

We installed all new chainplates,

bolts and nuts, clevis pins, mast tangs, and bow roller assembly made of tita- nium. One immediate problem was the brilliant shine of the chainplates sticking up from the deck. They sud- denly made the paint job on our boat look terrible. A sandblasted finish for the chainplates is available, and this might be a good option for the owner of an older boat. Over the past 6 years,

the money we have not paid to insurance companies has been reinvested in continually upgrading electronics and safety equipment on our floating home. A new rig with a foundation in titanium will certainly keep us safer and stronger than ever before. I only wish we were wiser and made the titanium upgrades before our rig came down.

Patrick Childress completed his first circumnavigation in 1982 in a souped-up 27-foot Catalina. He and his wife, Rebecca Childress are currently sailing in the Pacific, continuing on their west-about circumnavigation contact Allied Titanium, 800/725-8143, http://www.alliedtitanium.com

Maggi Chain USA, New Electronic Charts, AMT Composites for Fiberglass

Indian Ocean Crossing, The Preparation

Related Images:

Like this:

Like Loading...

Article about our dismasting

Article about our dismasting

Then in Part 2, Patrick shows how he modifies the hole that the titanium Chainplate passes through the deck through. He puts down plastic laminate to redirect any water that may ever find its way through that hole, to run on top of the Formica rather than under, and in to the wood.

Then in Part 2, Patrick shows how he modifies the hole that the titanium Chainplate passes through the deck through. He puts down plastic laminate to redirect any water that may ever find its way through that hole, to run on top of the Formica rather than under, and in to the wood.

Here is most of the article in text, without photos, in case your internet doesn’t allow the photos above, or if the link doesn’t work.

Here is most of the article in text, without photos, in case your internet doesn’t allow the photos above, or if the link doesn’t work.